Introduction

A fundamental problem in electrical engineering is sending messages over noisy channels. For example, all messages sent over the internet have to eventually be transmitted over physical channels (copper wires or fiber optic cables), and these channels can be damaged by the elements (eg. sharks)

I recently came across a method to reduce this problem to a purely mathematical one: the sphere packing problem, which aims to find the densest packing of non-overlapping \(n\) dimensional spheres in a given space.

Signals and Code

But first, let’s define the noisy channel problem more formally. Let \(T > 0\) be a fixed length of time corresponding to the length of a signal transmission.

A signal is a continuous function \(s : [0, T] \to \mathbb{R},\) where \(s(t)\) is the amplitude of the signal at time \(t\), and the frequencies do not surpass some fixed limit \(W\). Think of \(s(t)\) as the voltage of the signal at time \(t\) (for copper wires), or the intensity of a light signal at time \(t\) (for fiber optic cables).

A code is a finite set of signals \(\{s_1, s_2, \ldots, s_n\}.\) This can be thought of as a symbolic alphabet for two computers to communicate over a channel. A simple example of a code is \[ \{ s_1(t) = 1,\; s_2(t) = -1 \}, \] which can be used to send binary messages over a channel.

The Shannon–Nyquist Sampling Theorem states that any signal \(s(t)\) with frequencies less than \(W\) can be uniquely represented by a finite set of samples \[ \left\{ s(0), s\!\left(\tfrac{1}{W}\right), s\!\left(\tfrac{1}{2W}\right), \ldots, s\!\left(\tfrac{n-1}{2W}\right) \right\}, \] where \(n = 2WT\). This means that we can represent any signal \(s(t)\) as a vector \(\vec{s} \in \mathbb{R}^n,\) and any code as a finite subset \(C \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n\), where each element of \(C\) represents a signal.

The continuous signal above \(S(t)\) represented by the discrete samples \(S_i\). Therefore, we will represent a signal as a vector in the remaining discussion.

The Noisy Channel

In the real world, the sent signal \(\vec{s}\) is almost never the same as the received signal \(\vec{r}\). This is because the channel introduces noise, which we model as a random perturbation in the input.

Formally, we assume that the received signal is \[ \vec{r} = \vec{s} + \vec{z}, \] where \(\vec{z}\) is a random vector with Gaussian entries (each \(z_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\) and is i.i.d). If the receiver wants to determine which signal was sent, a natural decoding strategy is nearest-neighbor decoding: \[ \hat{\vec{s}} = \underset{\vec{s_i} \in C}{\text{argmin}} \| \vec{r} - \vec{s_i} \|_2. \]

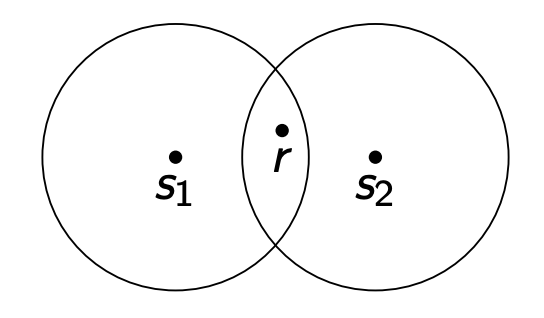

However, if two signals in the code are too close together, noise may make decoding ambiguous. For example, in the following situation:

which signal does \(\vec{r}\) correspond to? Both \(\vec{s_1}\) and \(\vec{s_2}\) are equally likely.

To solve this problem, remember that we assumed \(\vec{r} = \vec{s} + \vec{z}\) and that each \(z_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\). A fundamental property of the Gaussian distribution is that \[ \mathbb{P}[-3 \sigma \leq z_i \leq 3 \sigma] \approx 99.7\% \] So, we can use this to figure out a bound on the distance between \(\vec{r}\) and \(\vec{s}\) with high probability. In the worst-case, each component is such that \(|z_i| = 3 \sigma\). Since we have \(n\) components, this means that \[\begin{align*} \| \vec{r} - \vec{s} \|_2 = \| \vec{z}\|_2 &= \sqrt{\sum_{i = 1}^{n} z_i^2} \\ &\leq\sqrt{\sum_{i = 1}^{n} (3 \sigma)^2} \\ &\leq \sqrt{n \cdot 9 \sigma^2} \\ &\leq 3 \sigma \sqrt{n} \end{align*}\] with probability \(99.7\%\). This means that the worst-case noise can push the received signal \(\vec{r}\) up to a distance of \(3 \sigma \sqrt{n}\) away from the true signal \(\vec{s}\). This creates a sphere of radius \(3 \sigma \sqrt{n}\) around \(\vec{s_1}\). To make our decoding as unambiguous as possible, we need to ensure that even when noise pushes \(\vec{r}\) to the edge of this sphere, it is still closer to \(\vec{s}\) than any other signal \(\vec{s_2} \in C\). But signal \(\vec{s_2}\) also has a sphere of radius \(3 \sigma \sqrt{n}\) around it. Therefore, to guarantee that two spheres don’t overlap, the minimum distance between any two signals must be at least \(6 \sigma \sqrt{n}\)

Dense Sphere packing

Now, you might ask: why don’t we just pick signals that are as far apart as possible? For example, we could place just two signals at opposite ends of our signal space.

But recall that a signal \(\vec{s}\) represents the amplitude or voltage of a message over time. Physicists have told us the power of a signal is proportional to the square of its amplitude: \[ \text{Power} \propto \|\vec{s}\|_2^2 = \sum_{i=1}^{n} s_i^2 \]

In practice, we cannot transmit signals with arbitrarily large power. There are physical limits on how much voltage we can apply to a copper wire and how much light we can send through a fiber optic cable. If we set a maximum power budget \(P\), then all our signals must satisfy \[ \|\vec{s}\|_2^2 \leq nP \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \|\vec{s}\|_2 \leq \sqrt{nP} \]

This means all our signals must lie within a sphere of radius \(\sqrt{nP}\) in \(\mathbb{R}^n\), which is a compact region. The more signals we can fit in this region, the more information we can transmit per signal. For example, a code with 2 signals transmits only 1 bit per transmission, but a code with 256 signals transmits 8 bits per transmission.

At the same time, each signal needs a sphere of radius \(3\sigma\sqrt{n}\) around it to ensure correct decoding with probability \(99.7\%\). This is exactly the sphere packing problem: what is the maximum number of non-overlapping spheres of radius \(3\sigma\sqrt{n}\) that we can pack inside a sphere of radius \(\sqrt{nP}\)? Each sphere center represents a signal in our code, and finding the densest packing directly gives us the code that can transmit the most information reliably. Therefore, the problem of designing optimal codes for noisy channels reduces to an entirely abstract problem in math.